And Yet it Moves: Status of PBR in Mexico

- Enriqueta Molina, Santamarina y Steta

- Aug 15, 2017

- 6 min read

In a changing world, where change is the only constant, innovation is the key to face the challenges of agriculture for competitiveness, productivity, efficiency, value chain, business models and customer satisfaction. All these elements should be considered, in addition to cost reducing, optimize resources and environmental sustainability criteria.

Plant breeding is always searching for new and better responses to these questions. But sometimes regulations and institutional capacities are not moving at the proper speed.

Mexico is a land of opportunities for agriculture. It has the tenth place in world food production. Agricultural commerce in 2016 reached the sum of USD $54.8 million, with a positive balance of USD $3,275 million, and rising.

With 26.9 million hectares for agriculture; two agricultural cycles and 6 million of farmers, Mexico is ranked in 15th place of world economies (USD $1,064 billion).

Mexico has free trade agreements with 46 countries and 6 economic complementation agreements; 85 airports (3rd place in the world) and air-bridges to Europe, Asia, North-America, Middle-East, among others.

Mexico is considered a megadiverse country, given its greatest number and diversity of species: around 25 thousand of vascular plants; climates from tropical to desert, and not just biological richness: the cultural values linked to this, with a strong heritage of traditional knowledge to use this huge biodiversity.

Mexico is center of origin, diversity and domestication of many important crops and others insufficiently explored, such as: maize, beans, tomato, squash, cacao, chili pepper, amaranth, avocado, papaya, cactus pear, dragon fruit, guava, vanilla, agave, sweet potato, husk tomato, chayote, cotton, physic nut, jojoba, hawthorn, mamey sapote, pecan nut, purslane, dahlia, poinsettia, marigold and a very long list.

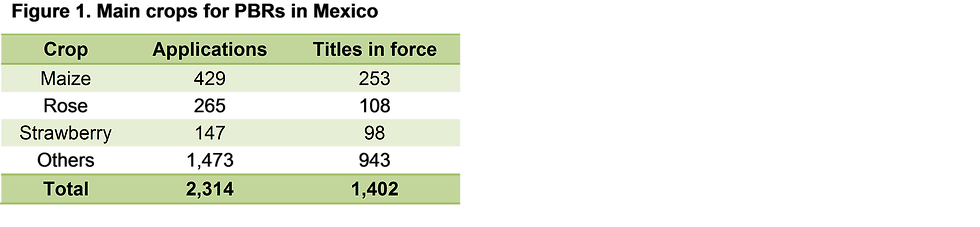

However, after 20 years of the enactment of the Federal Law of Plant Varieties, just 1626 titles were granted, a third part to domestic breeders, mainly to maize (19%), rose (11%) and strawberry (6%) [Figure 1]. Considering that there are more than 100 thousand titles in force in the world according UPOV statistics, there is an area of opportunity considering the national potential and research programs, and the comparative advantages for agricultural and food production.

PBR Status

The Plant Variety Federal Law (1996) establishes the procedures for plant variety protection, providing faculties to the Ministry of Agriculture, and particularly to SNICS (Mexican Service of Seed’s Inspection and Certification) for the management and enforcement of PBRs. The protection is for all plant genera and species, for a period of 15 to 18 years according to UPOV 1978.

From 1996 to 2016 a total of 2,314 applications of 133 varied species have been filed; at the end of 2016, 1,402 titles were in force for 97 species from 26 countries.

By their origin, 39% of the applications are from US breeders, 28% from Mexico, and 18% from Netherlands. Grouping them by continent, 27% comes from Europe. There are 255 applicants [Figure 2].

The main number of applications is for agricultural (29%) and ornamental crops (23%). Recently, the interest in berries is increasing, since the production of fruit has tripled in the last ten years [Figure 3].

The most important Mexican breeders are public institutions, research centers and universities [Figure 4]: INIFAP (Mexican Institute for Agricultural, Forest and Livestock Research), with more than a half of the Mexican varieties and 14% of the national total. Recently the Chapingo Autonomous University (Universidad Autónoma de Chapingo), has increased its participation, with 64 applications and 38 titles in force [Figure 5].

In the case of farmers, independent researchers and natural persons, they have registrations for varieties of avocado, cacao, maize, barley and bougainvillea.

These numbers reflect the growing development of national plant breeding programs, as well as trends in agricultural production.

They show an increasing number of stakeholders, expanding the technological offer to enhance farmers capabilities in benefit of the rural sector.

And demonstrate the actual and potential market that requires technology for a more competitive production, with plant varieties which could offer better conditions of adaptation, performance and value.

Enforcement

Twenty years after the start of the Plant Variety Protection (PVP) system in Mexico, it would be fair to review the regulations, which are according to UPOV 1978.

According to the current Federal Plant Variety Law, SNICS has the faculty to verify the compliance of PBR’s regulations by its own initiative. However, the actual procedure is that the breeder shall apply a formal request providing the information to identify the presumed offender who is suspected of using the protected variety without the breeder’s authorization.

SNICS values the information provided, and issues an agreement to schedule a verification visit with the purpose of confirming the compliance of the Law and their regulations. If during this verification it is proved any of the infringements stated by Law, SNICS may proceed to the seizure of goods. In practice, this doesn’t happen.

SNICS only prepares an inspection report, and the alleged offender has a period of time to provide evidences in his favor, and both parties can provide their arguments. The maximum fine is around 40 thousand US dollars. And after SNICS’s resolution it is possible to start a claim for damages.

The entire process with SNICS could take a couple of years –at least-, and is not the end. An appeal could be filed in the administrative court (there is an intellectual property chamber).

Therefore, you need patience… and specialized support.

It is fundamental that authorities understand that is not just legal certainty and enforcement of breeder’s rights (of course is legitimate and a just cause); it’s also a matter of order, quality and fair competition.

Harmonization and international trade

UPOV has 74 members, 3 in 4 are part of the 1991 Act. Several Latin-American countries have a regulation according to UPOV 1991: Colombia, Ecuador and Peru for instance, and the main trading partners with Mexico, such as USA, Canada and the European Union, among others.

Hence it is essential to consider the changes in agriculture, industry, economy, technology, market trends, and Mexico’s own experience on PVP after 20 years –and of course, after almost 40 years of UPOV 1978-, to review the regulations but also institutional capability to suitably respond to sector dynamism and ensure an effective enforcement system.

At the moment, two important trade agreements are under revision to modernize them: between the European Community and NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement, with US and Canada). It’s predictable that plant variety protection will be one of the topics to analyze and to call for harmonization and reciprocity.

Certainly it would be desirable for Mexico to accede to UPOV 1991, to extend the periods and coverage of protection (although training and clear explanations regarding concepts such as essentially derived varieties are critical).

But it’s necessary to go beyond these basic concepts: Mexico has the commitment to provide procedures and actions against any act of infringement of PBRs, regardless of the inclusion of the UPOV 1991 provisions.

It is fundamental to strengthen the enforcement measures to apply by the authority, simplifying, more expeditious and more effective, with stronger processes which really achieve the objective of preventing the infringing conduct, and where appropriately and effectively punishes those who make illegal use of protected varieties, inhibiting hostile and undeterred conducts.

Towards a new Law

Several legislative proposals have come and gone; the most recent project includes the UPOV 1991 provisions, its measures are stronger and stricter, and even criminalize the recurrence of an administrative offense, to persuade eventual infringers to avoid breaking the law.

SNICS has appeared unwilling to continue with this work, even when it is established on the goals of the Seed National System, updating and strengthening PVP law. Nowadays it seems that they are returning to this issue, under external pressure and with a close collaboration of breeders.

In the best scenario, with a new and stronger Law, this will not be enough.

To achieve the purpose of promoting innovation and to keep on building an effective system, other complementary elements are necessary, for example: institutional capacities should be improved with qualified personnel, clear and well-established procedures should be applied as well, also times should be shortened.

Collaboration between authorities and breeders in addition to a better communication strategy should be a regular situation, and not just a conjuncture or an eventual condition.

Divulgation campaigns and training for farmers, growers, local authorities, and all interested people could have an awareness effect to convince them about the benefits of protection, and to be conscious that illegal propagation implies a higher cost in fines, legal procedures and plaints, quality and phytosanitary effects, and loss of value and markets. Cheap can be costly.

There are some voices against this reform, and others are sleeping. Meanwhile, time moves on and technology, agriculture and commerce continue to progress.

The review and update of regulations, and the protection strategies on public policies are not an option. They are an obligation. Renew or die.

The increasing interest and investment on agriculture require regulations and competent authorities that meet the expectations of a competitive economy with a long-term vision.

Will Mexico finally go for it? We will see.

Comments